Transforming a classic

What a classic may or may not be is something

that makes for a splendid debate. The term which

we are now accustomed to using in the cultural

context is originally descended from the Roman

tax rights of the time of the Roman Empire. The

classis was a member of the highest tax class.

The adjective classicus is later used by the

Roman author Aulus Gellius (circa 175 A.D.) in

the discourse between literature and aesthetic.

From this point it appears in all areas of creative

activity. It has become the term used to describe

an art movement recognised as having created a

standard, a term however which is used indis-

criminately these days and is applied to repre-

sentations and works of various periods and the

widest range of genres. The term classic is often

used, in order to idealise periods of history. The

time that counts as the classical period of ancient

Greece falls between the Ionic uprising against

the Persian supremacy (500 B.C.) up to the

Peloponnesian war (up to 431 B.C.). It was in

this era that the groundwork was laid for western

philosophy, medicine, architecture, literature,

theatre and political constitution. Aristotle’s dif-

ferentiation between form and matter also dates

back to this time, a perception which may still be

as pertinent for design today. In Germany, when

people refer to the classical period, they usually

mean the literary classical period of the 18th

century, Wieland, Goethe, Schiller and Herder,

dialogical discussion between politics and aes-

thetics during the time after the French

Revolution. Or else it can mean the classical

music of Vienna, which was characterised by

Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven and which in the

meantime – because of its simplicity and popu-

larity – has quickly come to encompass several

historical music movements.

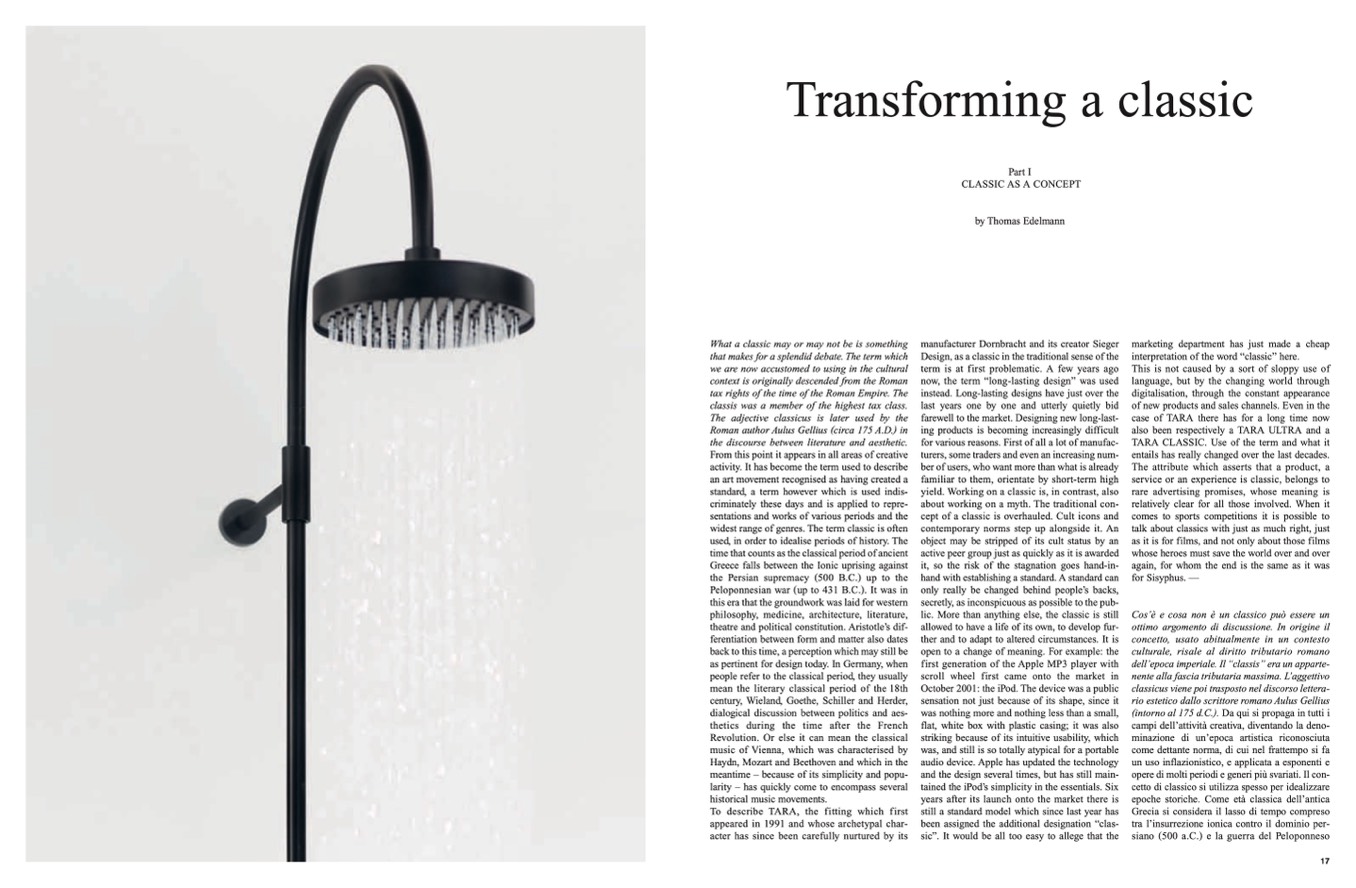

To describe TARA, the fitting which first

appeared in 1991 and whose archetypal char-

acter has since been carefully nurtured by its

Part I

CLASSIC AS A CONCEPT

by Thomas Edelmann

manufacturer Dornbracht and its creator Sieger

Design, as a classic in the traditional sense of the

term is at first problematic. A few years ago

now, the term “long-lasting design” was used

instead. Long-lasting designs have just over the

last years one by one and utterly quietly bid

farewell to the market. Designing new long-last-

ing products is becoming increasingly diff icult

for various reasons. First of all a lot of manufac-

turers, some traders and even an increasing num-

ber of users, who want more than what is already

familiar to them, orientate by short-term high

yield. Working on a classic is, in contrast, also

about working on a myth. The traditional con-

cept of a classic is overhauled. Cult icons and

contemporary norms step up alongside it. An

object may be stripped of its cult status by an

active peer group just as quickly as it is awarded

it, so the risk of the stagnation goes hand-in-

hand with establishing a standard. A standard can

only really be changed behind people’s backs,

secretly, as inconspicuous as possible to the pub-

lic. More than anything else, the classic is still

allowed to have a life of its own, to develop fur-

ther and to adapt to altered circumstances. It is

open to a change of meaning. For example: the

first generation of the Apple MP3 player with

scroll wheel first came onto the market in

October 2001: the iPod. The device was a public

sensation not just because of its shape, since it

was nothing more and nothing less than a small,

flat, white box with plastic casing; it was also

striking because of its intuitive usability, which

was, and still is so totally atypical for a portable

audio device. Apple has updated the technology

and the design several times, but has still main-

tained the iPod’s simplicity in the essentials. Six

years after its launch onto the market there is

still a standard model which since last year has

been assigned the additional designation “clas-

sic”. It would be all too easy to allege that the

marketing department has just made a cheap

interpretation of the word “classic” here.

This is not caused by a sort of sloppy use of

language, but by the changing world through

digitalisation, through the constant appearance

of new products and sales channels. Even in the

case of TARA there has for a long time now

also been respectively a TARA ULTRA and a

TARA CLASSIC. Use of the term and what it

entails has really changed over the last decades.

The attribute which asserts that a product, a

service or an experience is classic, belongs to

rare advertising promises, whose meaning is

relatively clear for all those involved. When it

comes to sports competitions it is possible to

talk about classics with just as much right, just

as it is for f ilms, and not only about those f ilms

whose heroes must save the world over and over

again, for whom the end is the same as it was

for Sisyphus. —

Cos’è e cosa non è un classico può essere un

ottimo argomento di discussione. In origine il

concetto, usato abitualmente in un contesto

culturale, risale al diritto tributario romano

dell’epoca imperiale. Il “classis” era un apparte-

nente alla fascia tributaria massima. L’aggettivo

classicus viene poi trasposto nel discorso lettera-

rio estetico dallo scrittore romano Aulus Gellius

(intorno al 175 d.C.). Da qui si propaga in tutti i

campi dell’attività creativa, diventando la deno-

minazione di un’epoca artistica riconosciuta

come dettante norma, di cui nel frattempo si fa

un uso inflazionistico, e applicata a esponenti e

opere di molti periodi e generi più svariati. Il con-

cetto di classico si utilizza spesso per idealizzare

epoche storiche. Come età classica dell’antica

Grecia si considera il lasso di tempo compreso

tra l’insurrezione ionica contro il dominio per-

siano (500 a.C.) e la guerra del Peloponneso

17